Chinese Calligraphy, Abstract Art, Mind Painting

Chinese Calligraphy, Abstract Art, Mind Painting

Ngan Siu-Mui, 1998

Chinese, English, French

ISBN 2-9805904-1

Acknowledgments

This book was written for the educationally oriented "Chinese Calligraphy, Abstract Art, Mind Painting" exhibition by Ngan Siu-Mui and her School held at Plateau-Mont-Royal Culture House in Montreal. The above exhibition together with the 7th Anniversary International Calligraphy Union Exhibition held between May and June 1998 at Frontenac Culture House and the Foung Cheung Museum of Traditional Chinese Art, were parts of the series of activities in the Month of Chinese Calligraphy in Montreal. The publication of this book was finanded jointly by the Ministry of Culture and Communications of Quebec and the city of Montreal under the l'Entente sur le développement culturel de Montréal as well as the Ministry of Canadian Heritage under the Program fo Support to the Official Languages. For the publication of the book, I am particularly indebted to the following individuals:

- Mrs. Louise Beaudoin, minister of Culture and Communications of Quebec.

- Mrs. Johanne Lorrain, member of the Executive Committee of the City of Montreal.

- Mrs. Sheila Copps, minister of Canadian Heritage.

- Mr. Laurent Legault, cultural agent, Frontenac Culture House.

- Mrs. Johanne Germain, cultural agent, Plateau-Mont-Royal Culture House.

- Mr. Gilles Vincent, Director of Botanical Garden of Montreal, for writing the preface.

- Mrs. Nicole Chenur, vice-president of the Traditional Chinese Culture Society of Montreal (SCCT) and co-directorof the Foung Cheung Museum of Traditional Chinese Art, for her work in applying f9or government subventions and for the French translation.

- Mr. Claude Tricot, honorary president of the SCCT, for his assistance in the French version.

- Mr. John Ho, co-director of SCCT, for his English translation.

- Mrs. Linda Prenoveau, co-director of the Foung Cheung Museum of Traditional Chinese Art, for her assistance in the English version.

- Mr. Yves Prescott for his assistance in the English translation.

- Mr. Truong Minh-Duc, vice-president of the Foung Cheung Museum of Traditional Chinese Art, for his technical support with the computer work.

- Mr. Barry Asgrodney, social dance instructor, for his professional advice on the material in chapter 4.

Preface

At last, a book on Chinese calligraphy that is bound to appeal to experts and laymen alike. For the latter, this compelling work goes beyond the cataloguing of the technical aspects, which are so hard to master for most of us. In fact, it is through her simple style and relevant examples that the author succeeds in furthering our understanding of the fascinating world of Chinese calligraphy. The comparison between calligraphy an social dance is highly appropriate as it stresses the fact that not only the fingers, but the whole body is involved in the creative act. As is the case in social dance, graceful and harmonious movements are to be sought by the calligrapher.

By reading this book, we gain insight into the subtle compromise which exists between the need to create original works on one hand, and the necessity to find inspiration in tradition on the other hand. Writing an authoritative book on Chinese calligraphy cannot be achieved withour a comprehensive approach, a perfect mastery of basic techniques and a deep knowledge of Chinese characters. Author Ngan Siu-Mui possesses these skills, being a world-renowned artist herself. Her writing style shows all the passion and fascination she feels towards this art form which traces its roots thousands of years ago.

It is through her fiery style that the relationship between Chinese calligraphy and nature become crystal clear. Reading of this book should allow nature lovers to broaden their understanding of the world around them, and more specifically of its spiritual dimension.

This book is a major contribution to the study of Chinese culture; by sharing her "secrets", the author contributes to our ability in assessing thescope of one of the great culture of mankind. There is indeed no better way to understand and appreciate Chinese culture than through its artistic heritage.

This book is a "must" to those wishing to familiarize themselves with Chinese calligraphy and its philosophical foundations.

Thank you Ngan Siu-Mui. You have given a precious gift to those wishing to know more about the world we live in. ❞

Gilles Vincent. Director of Montreal Botanical Garden, 1998

About the Author

Born in Hong Kong in 1947 and now a Canadian citizen, Ngan Siu-Mui is renowned in the Chinese art circle for her versatility in poetry, calligraphy, painting and seal carving. Her artworks have been collected by many museums, including the National Museum of Canada and the National History Museum of Taiwan. She was invited to participate in the All-China Exhibition of Famous Modern Artists, in Taiwan. Also, the Federation of Chinese Cultural Renaissance and the Calligraphic Association in Taiwan invited her as a distinguished calligrapher to participate in the International Calligraphic Conference and Exhibition in Taiwan. Since 1980, she has held many exhibitions. She has given demonstrations, workshops and lectures at the Malaysian Institute of Arts, at the University of Saskatchewan, the University of Toronto, the University of British Columbia, the Royal Ontario Museum, McGill University, etc. She regurlarly joins the international calligraphic exhibitions and conferences in the Asian Pacific region. Her publications include The Art of Ngan Siu-Mui, The Art of Ngan Siu-Mui and Her Group. She is now the president of the Traditional Chinese Culture Society of Montreal, she also sits on the board of directors of the Foung Cheung Museum of Traditional Chinsese Art in Montreal and the International Calligraphy Union of Canada.

❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 ‒ Mind Painting – Creative Energy in Calligraphy

- Chapter 2 ‒ Chinese Calligraphy Scripts

- Chapter 3 ‒ The Calligrapher's Tools

- Chapter 4 ‒ Watching Lady Gong-Sun's Sword Dance

- Chapter 5 ‒ Calligraphy Techniques

- Chapter 6 ‒ Approach Through the Seal Script

- Chapter 7 ‒ Special Techniques for the Regular Script

- Chapter 8 ‒ Studying the Writings of Ancient Calligraphers

Detailed Table of Contents

- A more detailed table of contents ⮚ Here

❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖

Introduction

Mental Discipline

Chinese Calligraphy has always enjoyed an important position in Chinese Art. Historically, many philosophers and scholars loved it, not only as an art, but also as a mental discipline since progressing in this art demands both concentration and perseverance. Records of the past and of personal experiences of various calligraphers have asserted that if calligraphy was practiced for a long time, it would dispel boredom, dismiss worries and relieve emotional stress.

Ou-Yang Sau (1007-1072), one of the Eight Great Scholars of the Tang and Sung dynasties, was a leading official at the imperial court who had extremely complex duties. Yet, in his leisure time, he often practiced Chinese calligraphy. In one of his essays, he explained why he never abandoned it. “In my childhood, I had many hobbies, but upon reaching middle age I gave them up, either because they no longer interested me, or because I am physically unable to engage in them. The only one that remains, and in which my interest grows with the passage of time, is calligraphy… I therefore realize why so many scholars in the olden days have paid so much attention to it.”

The Two Levels

From an artistic point of view, the practice of Chinese calligraphy is the beginning of cultivation of the arts. It enables a learner to acquire a sharp perception of all things in the universe, from simple lines to complex forms and movements.

As an art, it can develop on two levels: the formal and the ideational (idea-image). Before entering into the ideational level to undertake lively calligraphic creations from inspirations, sparked by experience, a beginner should first tread upon the footpath to the formal one so as to gain competence in the Chinese brush manipulation of every stroke, the construction of each character and the composition of the whole piece of calligraphy. It is with these two levels in mind that the present book is written so as to help readers gain a correct and comprehensive perspective for the appreciation and study of this art.

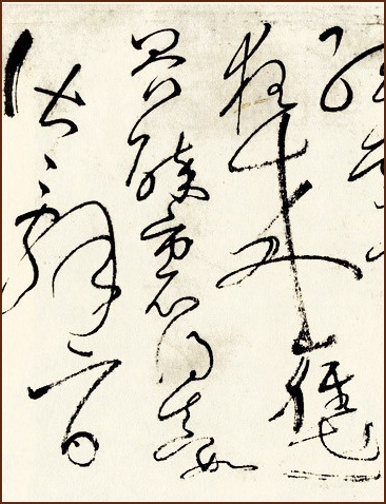

Cursive Script

~

"The fluttering Phoenix,

Not feeling contented,

Struggles to reach the blue yonder"

Calligraphy, Foundation of Chinese Painting and Seal Carving

The ideational level of Chinese calligraphy is like an endless alley along which we find unexpected experiences of delight and satisfaction, immensely enriching our lives. Moreover, if flexibly and discreetly modified, it can be applied to other artistic creations.

An example is that the Chinese brush manipulation techniques of painting are grounded in calligraphy. Hence, those familiar with the art speak of “writing” and not “drawing” a painting. Also, the seal carving art is fundamentally a variation of Chinese calligraphy. One must always remember that, without a solid foundation in calligraphy, artworks can hardly be great. Finally, quite a number of famous painters in the West have derived creative inspirations from the ideational level of Chinese calligraphy.

How to Appreciate Chinese Calligraphy

When they begin to learn calligraphy, many of my students, Occidental or Oriental frequently ask me this question: How can one appreciate Chinese calligraphy? Some of them even requested that I explain how in this book. However, due to limited space, and the impossibility of offering a brief explanation to such a vast issue, I can only hope that some day, if circumstances permit, it will be discussed in a companion book.

I can, for now, give you a glimpse of the answer as follows. Drinking Chinese tea or Western wine is a simple thing in our lives; however, to really appreciate a good tea or a good wine, one must frequently and carefully taste them. In the same way, the ability to appreciate the calligraphic art can only be cultivated from frequent and conscientious practice in writing and “reading”. For a beginner, learning only from a purely theoretical treatise is futile.

Creation and Tradition

If creative energy is considered an important element in appreciating Chinese calligraphy, attention has to be drawn to one very important principle: The criterion for assessing creations in Chinese art requires that all new ideas emerging in the artworks must be grounded in tradition.

However, from the Occidental contemporary view, art creations do not put stress on tradition. Moreover, if the weight of tradition is too heavy, the works are branded as pirated or as more copies. Hence, an enormous difference exists in the conception of artistic creations between Chinese and Western cultures.

At this age of constant reciprocal impact on both our cultures, the mission is arduous for the Chinese calligrapher who inherits and propagates tradition and, at the same time, strives for artistic freedom. The proper attitude should aim at absorbing and digesting the good qualities of the West, without losing sight of the traditional origin. Then, Chinese calligraphy can develop without being suffocated.

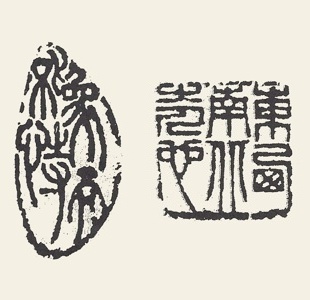

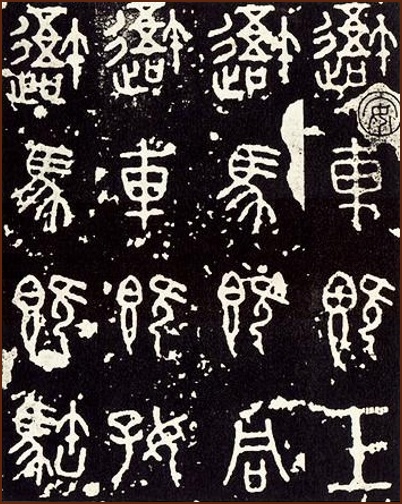

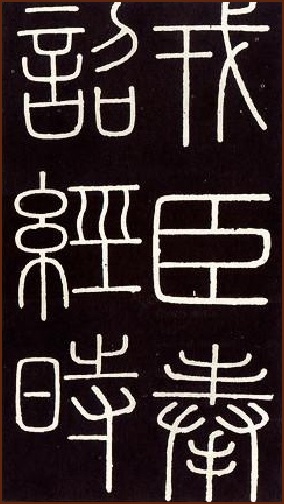

Seal Script Carvings

~

Yin Style

Seal Script Carvings

~

Yang Style

Composition in Chinese Calligraphy

The construction of characters and the composition of the whole piece of work have not been discussed at length, because of limited space. Rather, I elected to devote more space to better clarify the principles and techniques of Chinese brush manipulation. Thus, readers can understand the functions of each technique, thereby avoiding the drawback of having only the movement but not the desirable effect of the Chinese brush manipulation techniques.

To study the construction and composition of Chinese calligraphy without first understanding these techniques is as far-fetched as trying to build a castle in the air. Being part of construction and composition, the shapes of bold, slender, long and short Chinese brush strokes are accomplished by skillful brush movement, and are therefore the first thing to learn.

Jargon of Chinese Calligraphy

The traditional jargon used in Chinese calligraphy is often ambiguous, and to avoid unnecessary misunderstanding, that used in this book is slightly different.

Having said that, it must be remembered that there is a limit in describing complex movements. One has to bear in mind that it is insufficient to learn Chinese calligraphy merely from a book. A calligraphic demonstration is a more practical and effective means to understand. Finally, I reiterate that the aim of this book is to help readers gain a correct and comprehensive perspective for the appreciation and study of this art.

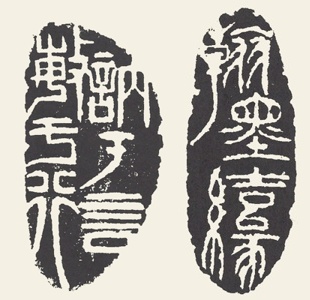

Seal Script Carvings

~

Yin Style

Chapter 1

Mind Painting ― Creative Energy in Calligraphy

Legendary Origins

According to literary records, Chinese calligraphy may be traced to as far back as over three thousand years ago. However, tradition claims that Chinese characters were invented five thousands years ago.

In ancient classics, it was recorded as follows: “Ancient writings were invented by Ts’ang Chieh, the official chronicler of the Yellow Emperor. With four eyes and maintaining communion with the deities, Ts’ang Chieh looked up in the sky and noticed the round and curved shapes of the Constellations. He also stooped down to examine the patterns on the shell of a turtle and the traces left by birds. By extensively collecting the diverse beauties of the universe, he assimilated them into writing.” The story also adds, “When Ts’ang Chieh was composing characters, husked rice fell from the sky and the ghosts wept in the dark of the night.” To this marvelous story, explanations were offered as follows:

- The secrets of creations could hardly be hidden from humans anymore, therefore it rained husked rice.

- Because spirits and deities could no more conceal their shapes, the ghosts wept at night.

Making Sense of the Legend

If we examine these descriptions carefully, we then understand that closeness to nature had great impact on the creation of the written language as an art. Why was Ts’ang Chieh portrayed as four-eyed? Because it was considered to be beyond the ability and intelligence of an ordinary person to create a written language ; “communion with deities” implied ones who had “intelligent” eyes.

Nevertheless, “Four-eyes” Ts’ang Chieh became a representative of the multitude, and by observing many things in the universe, he uncovered the mysteries of the arts in nature, which went unnoticed by the common people. Hence, heaven and earth were astounded.

Cursive Script

~

"I aim at flying and capturing

nature's movement in my calligraphy.

This seems to be my idea-image."

Beginnings of the Chinese Brush

On the other hand, it was not until the Shang dynasty (1766 BC – 1122 BC) that Chinese brush was adopted for practical use. Soft and pliable, the hair of a brush facilitated greatly the evolution and perfection of the daily writing techniques into the specialized art of calligraphy.

Evolution of Chinese Calligraphy

Furthermore, during the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD), the styles of calligraphy successively underwent evolutionary changes from seal into clerical, cursive, running and regular scripts. During this dynasty, basically all calligraphy scripts had reached their appropriate levels of distinction. In addition, the invention of paper-making by T’sai Lun was decidedly a major event in the developmental stages of the Chinese calligraphy, since the sensitivity of the paper matches perfectly with the softness and pliability of the hair of the Chinese brush.

Discoveries Through Observation

Moreover, at different times in history, many have been fond of oddities. They explored the multifarious changes in surrounding objects; fathomed their minuteness and wonders, and finally obtained wonderful results. These discoveries transformed into inspirations for Chinese calligraphy creations – what could be called “idea-images”.

Simply speaking, with their personality, sentiments, culture and education, the ancient calligraphers quietly observed the forms and movements of all the things in the universe. They then transformed their observations into idea images, the very soul of Chinese calligraphy, which was revealed in the strokes.

For example, Wei Fu-Jên of the Tsin dynasty (A.D.265-420) described the calligraphic strokes as below:

- Dots as “falling rocks from the summit of a high mountain”

- Horizontal strokes as “an array of clouds of a thousand mile”.

Zhang Xü of the Tang dynasty progressed significantly in his cursive script after seeing the sword dance by Lady Kung-Sun. By observing the wondrous peaked-like summer clouds, flying birds leaving the wood and frightened snakes entering into the grass, Huai Su (725-785) of the Tang dynasty was inspired to develop the Chinese brush techniques of cursive script. Yet, the shapes and movements of strokes are objects or realities in abstraction, rather than a concrete rendering.

Idea-Image

On the idea-image of Chinese calligraphy, T’sai Yung of the Han dynasty offered this insightful explanation: “The substance of strokes must have ‘shapes’, such as:

- sitting and walking;

- flying and moving;

- going and returning;

- lying and rising;

- sorrow and happiness;

- a worm eating leaves;

- a sharp sword and a long spear;

- a sturdy bow and a strong arrow;

- water and fire; clouds and fog;

- the sun and the moon.

Hidden Shapes of Strokes

In short, all strokes must have hidden shapes, and then they can be called Chinese calligraphy.” Phrases such as ‘sitting and walking’ connote the moving changes. To say that the sword is sharp; the spear, long; the bow, sturdy; the arrow, strong seeks to emphasize more than their mere shapes. As for water and fire, clouds and fog, these have shapes although not definite. Though the sun is round and the moon is hooked, if there are no spirit and characteristics, they are insufficient to represent the sun and the moon. This clarifies that the idea-images displayed in Chinese calligraphy are hidden shapes, taken from nature, and the experience of daily lives, and are therefore not based on abstractions.

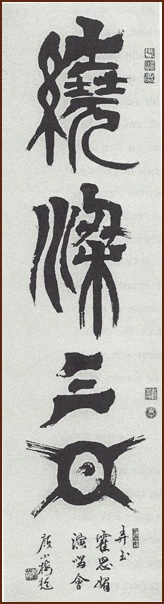

Clerical-Seal Script

~

"The Singer's Voice Reverberat

in the Chamber

for Three Days"

This calligraphy was written as the only decoration for a solo concert given by Mme Louise Forestier. During its creation, Ngan Siu-Mui, inpired by a wonderful voice resonating in a magnificent building, developed a style in clerical-seal script.

A Speedy Approach

With the advance of the material culture, people nowadays, are generally not interested in spiritual life. They are also estranged from contacts with Nature. Consequently, the path to exploring idea-images from all the things in the universe is bound to be arduously long and difficult to follow.

One might as well adopt a more effective and speedier approach to practice calligraphic skill by studying the writing of ancient calligraphers, of which two kinds of reproductions exist: Chinese rubbings from the steles and handwriting. This way, idea-images will be understood; wisdom and spirituality should develop, resulting in the conceptualization of surrounding beauty into idea-images, which in turn enliven Chinese brush movements. Then, personal feelings such as happiness, sorrow and anger can well be expressed, and the calligraphy will become a lively creation.

Ancient Calligraphers

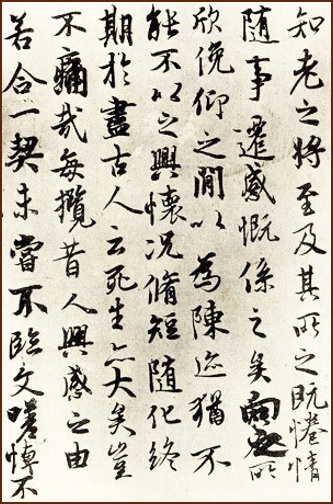

For instance, the tempestuous and impassioned Chinese brush strokes of the running script in the famous Elegy for a Nephew by Yen Chen-Ch’ing (709-785), of the Tang dynasty, renders an atmosphere of sorrow and resentment.(below)

Whereas, the running script in the Poetic Rubbing about the ‘Cold Meat’ Festival in Wong Chau by Su Tung-P’o (1037-1101), of the Sung dynasty, reveals an outburst of poetic sentiments.(below)

These examples show how Chinese calligraphers can display, with superior skill, their states of mind into idea-images. Hence, Chinese calligraphy has been called ‘mind painting’ which, in the proper sense of the term, is not really painting but is a collection of written characters, in which the hidden shapes taken from nature are dimly present. Herein lies the distinctive feature of the art of calligraphy.

Underlying Techniques

The formation of idea images is no easy matter, and for these to be revealed in the Chinese brush strokes, a superior command of the relevant techniques is implicit. Suen Gwoh-Ting of the Tang dynasty said, “Although ways of application originate from oneself, the calligraphy rules remain, and a slight erroneous move could make a great difference in quality. Thoroughly understand the technique, then flexibility will ensue. Be precise in thinking, but skillful in manipulating the brush. Thus writing can be free, natural and spontaneous.

Ideas Precide Writing

Eventually, ideas precede writing, then calligraphy reaches a superior level.” Creations in Chinese calligraphy can scarcely lose sight of calligraphic techniques. The several thousand years of painstaking and unrelenting efforts of the Chinese calligraphers have crystallized into these remarkable insights. Calligraphic works produced without these techniques and spirit are not truly Chinese calligraphy and must be called something else.

Chinese Calligraphies Are Not Pictures

Note that, in ancient times, there were styles of writing which used several patterns, such as dragon, snake, cloud, turtle and crane, overtly portraying their shapes; they were soon clearly defined as pictures and not Chinese calligraphy. Calligraphy must succeed in writing out characters with its distinctive techniques. The highest artistic expression in calligraphy consists in applying the strokes to describe the shapes and movements of all things in the universe – the idea images – thus producing a mind painting.

Mastering the Chinese Brush

Without masterful skill in the use of the Chinese brush, one lends oneself to the attitude and practice of “letting the brush move freely and letting the ink expand at random”, and then to claim these “loose works” to be idea-image creations. To do so means to spend one’s time and energy in vain.

On the other hand, the mere pursuit of the external beauty of written characters, to the sheer neglect of composing idea-images, result in simply “formal calligraphy”, dull and uninteresting as artworks. Nonetheless, traditional basic techniques are still retained in formal calligraphy, whereas loose work, if it becomes too widespread, could cause the extinction of this art. Devotees in Chinese calligraphy should therefore keep in mind its proper perspective.

Running Script

~

"Elegy for a Nephew"

Running Script

~

"Cold Eat Festival in Huang Zhou"

Chapter 2

Chinese Calligraphy Scripts

Unification of Chinese Writing

Contemporaneous with the political scene of the long period of annexation by feudal lords in the Warring States Kingdom (403-221 BC), a provincial diversity emerged in Chinese writings. Under the reign of the Ch’in dynasty, for administrative convenience, all calligraphy scripts incompatible with that of the former Ch’in State were abolished and fell into desuetude.

Chinese writings were then unified. Prior to the Ch’in Empire, calligraphy script as a term was non-existent, and it was not until Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD) that it was adopted for differentiation, since, at the time, the developments of all its variant styles had basically reached fruition.

Classification of Chinese Calligraphy Styles

In chronological order of evolutionary changes, chinese calligraphy is divided into seal, clerical, cursive, running and regular scripts (some say in the order of seal, clerical, cursive, regular and running).

Seal Script

In a broad sense, all kinds of writings previous to the Chin dynasty were named “great seal” and the unified writing of the dynasty was “small seal”; they are both seal script. Among the former, the writings on oracle bones and bell tripods of the Shang dynasty (1766 –1123 BC) were the earliest and the most important specimens of this script discovered so far. However, they were not written with brush and ink. Though not the earliest Chinese writings, “oracle bone script” served as a fairly advanced recording tool, and its characters numbered about five thousand. Some of the characters on turtle shells or animal bones seemed to have been written first with a Chinese brush, and then carved with a knife. Other characters were engraved directly with a knife. Wine tripod vessels used in ceremonial rites and bells serving as musical instruments were amongst the most significant brass vessels in which “bell tripod script” were inscribed, either by casting or by engraving.

Clerical Script

To facilitate daily writing, the small seal script was gradually modified, firstly into the “ancient clerical script”, and secondly, into the clerical script during the Han dynasty (B.C.206-A.D.220). Its distinctive characteristics were:

- The end of a long horizontal stroke stretched rightward in a wavy form, known as “the wild goose tail”

- The beginning of long horizontal strokes which resemble a “silkworm head”.

- The shape of a character was developed from the vertically rectangular shape of seal script into the horizontally rectangular or square one.

- Angular strokes were used extensively. Hence, horizontal and vertical connecting strokes of the seal script were changed from round turns into angular and broken ones.

Cursive Script

Although the flow of the brush was smooth, writings in this style were not easily identifiable, due to the undue simplification in brush stroke. This script fell into three styles:

-

Compositional Cursive Script (Zhang Cao)

Again, to facilitate everyday writing the ancient clerical script of the early Han dynasty was gradually simplified into the compositional cursive script with the retention of the wavy form. All characters were separate from one another. -

Modern Cursive Script

Compared to the clerical script, the compositional cursive script was more convenient; but to further speed up brush flow, the wavy form was curtailed and brush strokes were suitably linked together, inspite of occasional breaks. Thus, not every character was isolated. -

Crazy Cursive Script

With the modern cursive script as its basis, the crazy cursive script was developed. Many brush strokes were generally linked together. A strong contrast was apparent, not only in the construction of each character, but also in the spacing of the whole piece in composition. The variation in the brush flow was so great that at times it reached a wild, frantic and liberal manner, without however departing from the accepted norm, thereby encroaching upon the stratum of pure art, quite detached from the level of practical value.

Running Script

The simplification of the clerical script, and the adoption of the linking strokes and the speedy brush flow of the cursive script resulted in the formation of the running script. It was further modified into a style intermediate between the cursive and regular scripts, under the influence of the latter.

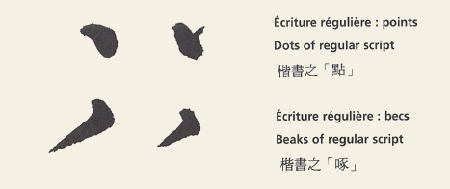

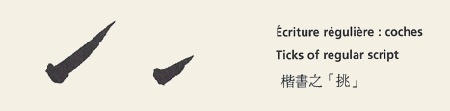

Regular Script

Changing the rightward projection of the “wild goose tail” from the clerical script into what the Chinese called a “Na”, and synthesizing the distinctive characteristics of the brush manipulation used in the cursive and running scripts with the production of a great number of dots, beaks, hooks and ticks resulted in the creation of the regular script. Faster and easier to write than the clerical script, it was more readily identifiable than the cursive and running scripts. Nowadays, both running and regular scripts are used everyday.

Evolution of Chinese Calligraphy

As Chinese writings have undergone complex evolutionary stages, it is difficult to specify the date when each calligraphy script emerged. Moreover, it is equally difficult to clearly demarcate and define all the transitional styles of calligraphy script.

Thus, the “ancient clerical script” was intermediate between the seal and clerical scripts; the "clerical-cursive script", between the ancient clerical and compositional cursive scripts; the “clerical-regular script”, between the clerical and regular scripts.

On the other hand, a style of calligraphy script, generated from artistic creation, at times emerged between two scripts. Thus, the “running-regular script” was essentially running but regular in appearance, while the “running-cursive script”, was running in substance but cursive in appearance. The illustrated diagrams show only the standardized forms of seal, clerical, cursive, running and regular scripts.

Chapter 3

The Calligrapher's Tools

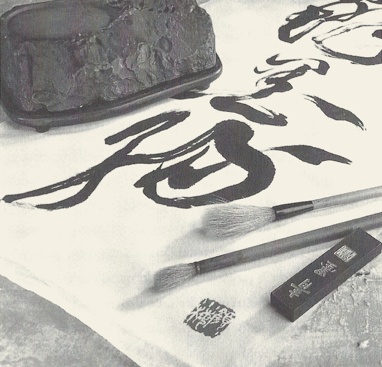

Brush, Ink, Paper, Inkstone

The Four Treasures: Paper, Brush, Ink, Inkstone

The Chinese brush, ink, paper and inkstone are collectively known as “the Four Treasures of the Room of Literature”. Good quality tools will reward the artist with better results. Good calligraphy tools are not necessarily costly.

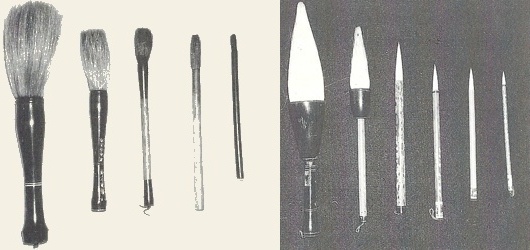

The Brush

Soft hair and hard hair brushes

A brush is made of animal hair, which may be soft, hard, or a mixture of the two. The soft hair of the sheep, the hard hair of the wolf, and the mixed hair of the leopard with the wolf’s, or that of the sheep and the wolf are all of good quality. Compared with hard hair, soft hair not only absorbs more ink, but is also slower in infusing ink. Generally, soft hair is the best material for writing. Although because of its softness, a beginner will find it difficult to control. He will eventually find it extremely helpful once he gets used to it. In fact, this is a very good training for strength regulation. If, however, a beginner is in the habit of using hard hair, the adaptation is difficult, once he changes to soft hair. However, mixed hair being neither too hard nor too soft, is also a good tool to start.

The Proper Size

The size of a Chinese brush depends on the character size. In general, a comparatively large brush should be used, so that the writing looks strong; consequently, a comparatively small one should not be used, otherwise the strokes will look weak. Thus, as a rule of thumb, character sizes between 3 and 5 cm2 can be written with a brush having a 2 cm tip in length. This may be used as a criterion in choosing the size of a brush. Note that the tip of a new brush usually contains some glue, which should be removed by soaking and rinsing in cold water.

Qualities of a good calligraphy brush

- The brush tip is pointed,

- The hair should be uniform in length,

- There is enough hair in the tip,

- The hair is pliable.

Different Sizes

The Ink

The ancients always had to grind the inkstick to make ink for writing. Nowadays, however, bottled ink of fine quality is readily available. If it is considered time consuming to grind the inkstick, bottled ink can be used instead. Although the effects of writing ink are less varied than those of painting, there are distinctions in its thickness, mildness, dryness and wetness. Generally, provided it does not adhere to the hair of the brush, thick ink is preferable to a light one. Thick ink is lustrous and lively. Light ink, on the other hand, can spread out too easily, changing the shapes of the strokes and lacking in vitality; but if properly controlled, amusing effects might be produced. In writing the seal, clerical and regular scripts, the ink should be thick, whereas in running and cursive, it must at times be thick, while at other times, thin.

The Paper

In terms of results,” Suen” paper, made in China, is the best. To practice calligraphy however, the cheaper Chinese “grass” paper may be used instead. Glossy or finely textured paper does not absorb ink readily and is not suitable for use.

The Inkstone

To prepare the ink, add some clean water to an ink-stone. Then dip an inkstick into it, grinding it vertically in circular motions until the water becomes creamy. Do not grind too forcefully, or else the resultant ink will contain some undissolved particles. After usage, the ink-stone must be washed, otherwise the ink residues will stick to it, and removal is difficult. Moreover, the ink-stone then becomes uneven and when grinding ink again, the shades of the ink will be dull and dirty, since the old ink is now mixed in with the newly ground one.

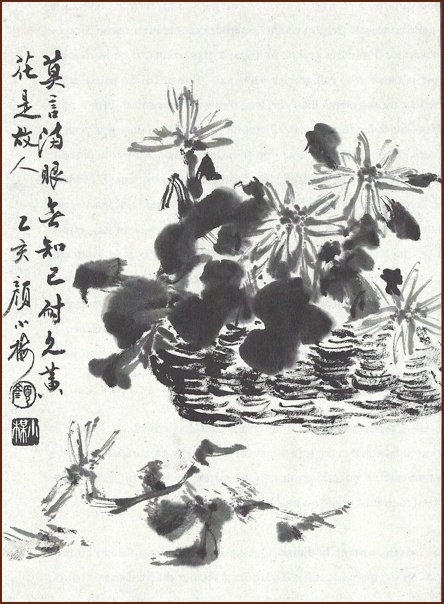

Chrysanthemum

~

"Don't say there is no eyeful bosom friend;

An enduring yellow flower is an old friend."

Chapter 4

Lady Gong-Sun's Sword Dance

Influence of Chang Hsü

The best known example in history where calligraphy and dancing were discussed together is related to Chang Hsü (Zhang Xu), outstanding calligrapher in the Tang dynasty. His cursive script technique advanced significantly after watching Lady Kung-Suen’s sword dance, inspiring his principle of the undulating stroke. He became famous for the creation of the “crazy cursive” script, which brought calligraphy into an impassioned artistic realm.

The multiplicity of his horizontal and vertical brush strokes, and their unending possibilities may be likened to sudden thunder and lightning which instantaneously flash for thousands of miles. As his calligraphy style appeared unrestrained, he was nicknamed “Crazy Chang”. Nevertheless, though crazy, his calligraphy rested on traditional techniques, and it exerted a far-reaching influence on future calligraphers. His legacy was later perpetuated by the “mad monk”, Huai Su, who eventually developed his own style of “crazy cursive” script, thereby winning the reputation of “the Mad Inheriting from the Crazy”. Both of them were honored as the “cursive sages”.

Calligraphy and Dancing

If we follow the idea-image discussed in Chapter 1, it is easy to imagine that the dancing movements of Lady Kung-Suen are, to a great extent, represented in Chang’s cursive script. Thus “as agile as a wandering dragon”, “as swift as a frightened snake”, and “the inability to trace the diverse changing propensities” describe well Chang’s cursive script.

Both Chinese calligraphy and dancing are entrancing in the gracefulness of their movements. Of course, they differ in their medium of expression: lines on paper for calligraphy, postures for dancing. The posture of brush manipulation has a direct bearing on the quality of strokes described. To be sure, calligraphy as an art benefits one’s well-being, and helps relieve mental strain and nervousness.

The longer the practice, the more prominent its benefits for the mind. The reason why some beginners are unable to enjoy the pleasure and reap the benefits of calligraphy seems to lie in their ignorance of the posture of the brush manipulation. When comparing the lively and impassioned writings of the past with the dull and hackneyed calligraphy often found nowadays, one has the feeling that this art is on the decline.

In the hope of enabling readers to enjoyably grasp the posture of Chinese brush manipulation in calligraphy, I shall here attempt to compare the movement of calligraphy and social dancing, which is popular both in the East and the West.

-

Lead with the Body

In social dancing, the natural trend is that forward, backward, sideways or turning movements must always be led by the body, and followed by the feet, which should never take the initiative to move the body. This brings swift movements and a proper distribution of energy. Similarly, in Chinese calligraphy, the fingers must not be used to move the brush. Instead, depending on the size of the characters written, the strength and movement must be transmitted - from the wrist, the elbow, the shoulders or even the waist - to the fingers, which are merely used to hold the brush. This way, one can arrive at the stage where the strength of the whole body is exerted to write, as prescribed by the ancient calligraphers. Many specialized treatises on calligraphy give elaborate discussions on using the fingers to hold the brush, but very little on the body as the prime mover. Unaware of the principle that advises to “move the Chinese brush primarily through the body, the fingers serving only to hold it”, one is likely to sit or stand stiffly, not daring to move the body an inch, and moving the brush only with the strength of the fingers. This rigidity prevents moving agilely and flexibly. Calligraphy then becomes weak and lacks in spirit. -

Use the center of gravity

In dancing, it is necessary to alternate the feet in order to follow the body while moving forward, backward, sideways or when turning. Hence, when doing so, the dancer must stand firmly on one foot maintaining the center of gravity, and support the whole body, making it possible to move in all directions without losing one’s balance. In calligraphy, the Chinese brush can be compared to the single foot, and the strength (center of gravity) must be exerted at the point of its tip to make it stand solidly, thereby describing powerful strokes and enabling one to move freely in all directions. -

Take an advantageous position

In dancing, the body must assume an advantageous position. Since the end of one step becomes the start of another, the dancer must prepare for the beginning of the next step. Then, the movements are easy to execute, however varied they may be. For example, before turning, slightly turning the body first in the opposite direction will make the movement easier and give it more strength. In calligraphy, the brush point must also be in an advantageous position at the beginning and the end of the stroke to facilitate brush movements. As an example, the hidden stroke used at the beginning of a stroke must first go in a reverse position. In other words, if the stroke’s direction is to the right, move slightly to the left, and if moving downward, slightly raise upward. At this point, it is impossible for the brush stem to remain perpendicular to the writing paper. In short, it will incline leftward, rightward, or towards top or bottom of the paper. As another example, at the end of a stroke, the tip must again be held in an advantageous position to prepare for the writing of the next stroke. -

Return to the first position

On the completion of each section of dancing steps, both feet must return to their original position (close together or follow-through). This enables the dancer to move at ease in any direction without losing balance. Each stroke in calligraphy may be considered as a section of dance steps. When the tip of the brush travels to the end of the stroke, the hair of the tip must resume original shape, before starting another stroke. This prevents the hair from spreading out which would result in undesirable strokes. -

Orientation

In dancing, whether moving forward, backward, sideways or turning around, one must know beforehand the intended direction to ensure the body can move in that direction. In moving the brush, the direction must also first be known, so as to carry the brush point accurately from one stroke to another. Only then, can elegance be maintained for the strokes in each character, and can a nice composition be attained for the whole calligraphy. -

Sharpness in response

In dancing, the man and woman signal by hand or body contact. Hence, great importance is attached to the mutual arrangements of the hands, as well as the intensity of the pull or the push. Only appropriate contacts can initiate sharp responses, so that the dancing partners can match their steps, without the danger of moving in undesired directions. The calligrapher is the active partner, and the Chinese brush is the passive follower. Attention must be drawn to brush holding and manipulation, and to the degree of strength applied to it. Then, the writer can sharply respond to every little movement of the brush tip along the paper. This way, the strength and speed of brush manipulation can be adjusted as one pleases. -

Flow of rythm

There must be light, heavy, quick and slow movements in dancing, and this is the same in calligraphy. Dancing has to rely on musical rhythm and the dancer’s interpretation of it. In Chinese calligraphy, the different characters, styles and idea-images generate different rhythms. Moreover, in terms of rhythm, there is greater freedom in the latter, although it demands a high degree of planning. Generally speaking, the seal, clerical and regular scripts have a slower rhythm, but are less varied than the running and cursive scripts. If the flow of the brush is rhythmic, the brush strokes are then full of life and vitality. -

Delaying

In dancing, one has frequently to delay the footstep or follow through; in calligraphy, one has to delay the brush point. Delaying the footstep means to temporarily pause the foot in anticipation, so as to gain momentum from the ground to strengthen one’s movements. Delaying the point means to temporarily pause the brush, as though something stands in the way and must be fought against, before one can continue. This notion is in agreement with the ancient calligraphers’ opinion that the ability to generate the sound of friction when the brush glides along the paper is the result of brush delay. Its effect is to make every portion of the stroke sturdy and forceful. -

Straightness and curvature

There is no need to draw lines on the floor in dancing, however advance, retreat and roundabouts of footsteps should follow the locus of “straightness visible in curvature and curvature visible in straightness”. In calligraphy, if this principle is not properly adhered to, then the shape of every stroke, the construction of every character and the composition of the whole piece of work will lose the beauty of elegant flow. -

Suppleness

As in dancing, where the knees have to be slightly bent, in calligraphy, the finger joints must also be slightly bent outward when holding the brush to prevent stiffness, which would then show a lack of agility and flexibility in moving.

Brush Movements and the Whole Body

The above analogies are enough to demonstrate that Chinese calligraphy involves the whole body during brush movements. Although different brush manipulation techniques are introduced in Chapter 5, in its highest level of excellence, Chinese brush manipulation can reach the stage where the mind and the hand are mutually responsive. Then, one can reach the level where “the hand does not initiate movement but the wrist does; and the wrist does not initiate movement but the mind does”. Movement initiated by the mind is the highest artistic realm one can reach in calligraphy. That is what was mentioned in Chapter 1: the union of techniques with idea-image applied to brush manipulation. Even the very ordinary things in daily life can inspire the calligraphy. Of this, there were ample records in history:

- Cai Yong, in the Han dynasty, saw a mason brushing characters with slaked lime. He was so interested by what he saw that upon returning home, he invented the “Flying White” calligraphic style.

- Zhang Zu, in the Tang dynasty, reflected many delightful and surprising changes seen in heaven and on earth in his calligraphy. For example, after seeing a princess’ porters struggling to make way on the road, and hearing the blowing and beating of musical instruments, he evolved the methods and implications of the use of the brush.

- Yan Zhen Xiang, also from the Tang dynasty, used the marks on a leaking house to describe the naturalness and vitality of brush manipulation.

- Huang Ting Xian, of the Sung dynasty, saw a boatman rowing with an oar and understood the reason of bringing the brush tip to every part of the brush stroke.

- Xian-Yu Shu, also of the Sung dynasty, after seeing a chariot driver struggling in the mud, understood the effect of delaying the brush point.

- Ou-Yang Xiu, during the same dynasty, described T’sai Hsiang’s calligraphy as “if moving up a current, exhausting one’s energy, but still remaining in the same place”. This explains well the resistance produced by Tsai’s use of the brush delay technique, which he applied with remarkable effect in his brush strokes.

- Wen Tong, of the Sung dynasty, saw snakes fighting and understood how both Chang Hsü and Huai Su perceived the principle of the cursive script.

If we meticulously ponder over the experiences in creations by foregone calligraphers, surely there must be breakthroughs and discoveries in the practice and appreciation of calligraphy. At the same time, this reveals an important spirit of calligraphy: it is an art inseparable from real life whose happenings can be a source of inspiration for calligraphy creations.

Clerical Script

Cursive Script

Running Script

Regular Script

"Flying White" Calligraphy Style

Chapter 5

Chinese Calligraphy Techniques

Introduction

Generally speaking, the beauty of calligraphy is revealed in:

- The Chinese brush movement techniques

- The construction of each individual character

- The composition of the whole piece of artwork.

As the hair of the brush is soft and pliable, it can respond readily even the most minute movement. Brush movement techniques are means to control its softness and flexibility. Brush movements techniques include body posture, brush holding, position of the wrist, strength regulation and tip manipulation. These not immutable, they are subject to adjustments in response to the size of the characters and personal habits.

Posture

Body posture must be proper, so as to coordinate the movements of the fingers, the wrist, the elbow, the shoulders and the waist. When writing characters, the body should feel comfortable and at ease. Avoid standing or sitting rigidly. In general, characters above 10 cm2 should be written in a standing position. This will not only facilitate brush movement, but also widen the field of vision, which will then ease the construction of characters and the overall composition. The sitting position is suitable for writing smaller characters. Nevertheless, these two positions may be adopted to suit each individual. Following is the proper posture:

- Sit properly on a chair, but stand up when writing large characters. In either position, the feet rest level on the ground, 20 to 30 cm apart.

- In the sitting posture, the two forearms should be placed flat on the desk at an angle of about 45 degrees with the chest. The left hand rests on the paper, while the right hand holds the brush. In the standing position, the right wrist and elbow are suspended, while the left hand still rests on the paper. The two hands mutually balance the strength of the artist. While writing, the left hand, from time to time, moves the paper to a suitable position.

- The back and the waist should be upright, while the head is slightly inclined forward. Whether sitting or standing, the body does not lean against the edge of the desk.

- The paper is placed flat on a desk, perpendicular to the edge of the desk. The head should be facing the portion of the paper being used.

Brush Holding

If the brush is held properly, writing can be done freely. At the same time, the strength of the body can pass through the shoulders, the elbow, the wrist and the fingers to reach the brush point. This enables the drawing of powerful strokes. Holding the brush too tightly, however, inhibits its free movement; while holding it too loosely ends in shakiness and limpness of the hand. Here are the methods:

- Hold the brush stem firmly with the first phalanges of the thumb, forefinger and middle finger. Place the thumb horizontally, rather than vertically. This position keeps the palm of the hand empty to facilitate movement of the brush. The first phalange of each finger is very sensitive and readily feels any movement of the tip on the paper.

- With the small finger held in tight contact, the fingernail of the ring finger is pressed against the brush stem.

- To avoid holding the brush stem too stiffly, hook the five fingers around it, with the joints slightly bent outward.

- Hold the brush stem at a height corresponding to the size of the characters, with the thumb approximately 4 to 8 cm above the joint between the stem and the hair. Generally speaking, holding the brush higher on the stem gives greater freedom in brush movement, while holding it on the lower part brings more firmness and stability.

- Keep the stem directly in line with the nose, but slightly to the right-hand side.

- While writing, all five fingers contribute to hold the stem firmly.

Brush Holding

Essential Rules

-

Tightening the Fingers:

while writing, there must be no empty space between the forefinger, middle, ring and small finger holding the brush stem. -

Emptying the Hand:

this refers to emptying the palm which maintaining firm grasp of the brush stem with the first phalange of the fingers. -

Holding the Palm Upright:

either in a pillowed or raised wrist position, when writing small to medium-sized characters, hold the palm upright, and not level with the wrist. In a suspended wrist position, when writing big characters, the palm is held almost parallel to the paper. -

Levelling the Wrist:

the wrist should be parallel to the paper, so that the top of the brush-stem will be inclined towards the left to facilitate the use of the hidden-stroke technique. -

Keeping the Brush-tip Upright:

always keep the brush-tip upright, and not flat on the paper. This is the key to the flexible use of the central-tip technique. The idea behind this very important technique lies in keeping the tip upright, with one’s strength concentrating at the point, while the stem is permitted to slant towards any given direction. Please note that although always holding the brush stem vertical to the paper is central-stroke technique, but this makes it difficult to apply the strength of the artist.

Wrist Positions

In order to deliver the strength of the body to the point, so that it moves flexibly, it is very important to have proper wrist position.

-

Pillowed Wrist

In a sitting position, both the wrist and the elbow are in direct contact with the desk. With this, brush movements are not very flexible since only the fingers can move the tip. As such, characters larger than 2 cm 2 are difficult to write. -

Raised Wrist

In a sitting position, here, the elbow rests on the desk, while the wrist is raised. This way, not only can the brush be manipulated more easily, but also the strength is allowed to flow readily. Raise the wrist above the desk at a height proportional to the size of characters, the greater the characters the higher the wrist. This is most suitable for writing characters between 2 and 6 cm 2. -

Suspended Arm

Here, both the elbow and the wrist are lifted from the desk. If one is not used to it, the hand will shake and feel weaker. However, once skillfulness is achieved, the brush can be maneuvered most freely, with sufficient strength. This is suitable for writing characters above 6 cm 2 and can be done while sitting or standing. Write characters larger than 10 cm 2 , however, should be written while standing.

Moving the Brush

This technique refers to regulating the strength of the body, while maneuvering the brush. It varies in accordance with the size of the characters being written.

-

Wrist Movement

This is simply the action of moving the brush using the strength of the wrist. The elbow is positioned on the desk while the wrist is raised slightly with the forearm lying flat on the desk. It is suitable for writing character sizes between 2 and 4 cm 2. -

Elbow Movement

This means maneuvering the brush with the strength of the elbow which is positioned on the desk, while the wrist is raised at a height proportional to the size of the characters. The wrist and the fingers move along with the elbow. It is suitable for writing characters between 2 and 6 cm 2 in size. -

Shoulder Movement

This implies moving the brush using the strength of the shoulder; and, while the arm is suspended, the fingers, the wrist and the elbow move along with the shoulders. It is suitable for writing characters above 6 cm 2. -

Waist Movement

This brush movement is made possible by concentrating the strength of the whole body at the waist, while the fingers, the wrist, the elbow and the shoulders all move along with the waist. It is suitable for writing characters about 50 cm 2 in size. For writing very big characters, the calligrapher may even stand on the writing paper.

Using the Brush Tip

The key to correctly maneuvering the tip is to know how to handle the point while writing. The strokes are then powerful and can appear in many forms. If the whole brush-tip is pressed up to the stem on the paper, strokes will be rigid, monotonous, and therefore uninteresting. Furthermore, once completed, the strokes must not be corrected, otherwise the writing will be spiritless and weak. Hence, ‘ideas come before writing’, meaning it is necessary to understand first both the principle and the methods of using the tip, then the best results can be obtained.

Fundamental Techniques

Strokes

-

Hidden-Stroke

This technique prevents the undesirable appearance of a sharp point at the beginning of a stroke. Hence, make a “dot” first when starting each stroke then lift the tip slightly and move forward. For vertical strokes, when the intended direction is downward, move upward first a short distance, then move the brush over this stroke and go downward; and for horizontal strokes, when the intended direction is rightward, start by moving slightly leftward.- To take an advantageous position so as to transfer your power to the tip. Then the strength of the body can easily be sent out while moving forward. This means, inclining the top of the brush leftward, for instance, while moving its tip rightward, and upward while moving downward.

- To spread out the hair of the tip flatly before moving it rightward or downward. This makes the stroke even on all sides.

- To make a round or angular shape at the beginning of a stroke.

-

Central-Stroke

With the hair spread out evenly, the point moves along the center of a stroke. The stem can incline in all directions, with the strength falling within the point. Hence, the stem is not always vertical to the paper. The central-stroke is the principal Chinese calligraphy technique, and the resulting strokes will be thick, round, with a three dimensional appearance. Using the point to make central-stroke concentrates the strength of the writer’s body at the point; and, undoubtedly, the resulting lines are stronger and more forceful, even if they are as slim as a hair. -

Returned-Stroke

Move the tip to the very end of the stroke, raising it slightly to make the brush point return quickly back to the stroke. It serves three purposes:- To directly transport one’s strength to the end of the stroke.

- To finish the stroke in a round or angular shape.

- To enable the adoption of an advantageous position for the tip so that it can be moved with power in any directions, and also to prepare to begin another stroke.

-

Slanted-Stroke

Slightly incline the tip to start the stroke; but rapidly return to a central stroke to prevent it from lying on the paper, as a mop sliding on the floor. The slanted-stroke is used to write angular strokes. -

Exposed-Stroke

When the tip approaches the end of a stroke, rapidly lift, then move it outward with the gesture to return it to the stroke, in the air. By so#doing, a sharp point will appear at the end of the stroke, but still retaining its strength. An appropriate use of the exposed-stroke results in elegant movement. -

Angular and Round Strokes

Strokes where angles appear at the beginning, the end and the turn are said to be square. Those without an angle are called round strokes. Square strokes are drawn by slanting and pressing the tip, while round ones use the central and lifting-tip techniques. The strength of angular strokes is revealed externally, whereas that of round ones is concealed.

Fundamental Techniques

Movements

-

Lifting and Pressing

Lifting is to raise the tip, without leaving the paper, so as to write a very fine line. Pressing means to push down the tip, so as to draw a bold and heavy line. The use of these techniques will produce different effects:- to create round strokes, bold or fine in central-stroke;

- to create angular strokes, bold or fine in slanted-stroke;

- to adjust the tip from the slanted to the central position;

- to adjust the shape of the tip.

-

Speeding and Delaying

Speeding means to move the tip rapidly while writing, and is an important technique to show vitality. It should be noted that excessive speeding would result in imperfect shapes. Delaying is a gesture to slow down the movement of the brush, as though something stands in the way and must be fought against, before proceeding. This prevents the strokes from being too straight or weak. However, excessive slowing down will produce stagnant strokes. -

Turns and Joints

Use the slanted and pressing-tip techniques in making a turn in angular strokes, thereby creating a joint. To make a turn in a round stroke, use central and lifting-tip techniques.

Miniatures

Chapter 6

Chinese Calligraphy Approach Through the Seal Script

The Proper Script for Beginners

In chronological order of creation, calligraphy may be divided into seal, clerical, cursive, running and regular scripts. A beginner should first decide which calligraphy script to choose. Because of the overt exaggeration of their moving beauty, cursive and running scripts, attract a good number of persons, many of whom even attempt to adopt them to start learning calligraphy. However, since their brush techniques are complex, this is like trying to run before learning to walk, how, then, can one avoid falling down. Traditionally, there are two views on the proper calligraphy script for beginners: learning seal script vs. regular script. It is still undecided which is the right approach. As regular script is most complete in brush manipulation techniques and, as well, is the one practiced and used everyday, many beginners choose it. As a calligraphy teacher, I prefer the seal script in round strokes for beginners.

Seal Script

Ancient calligraphers often said that without some knowledge of the seal and clerical scripts, calligraphy could hardly reach the superior level, therefore, it is necessary to learn them. A good knowledge of brush manipulation is prerequisite for a beginner. Although the composition is unique in each of the five calligraphic scripts, they are inseparable in terms of the brush manipulation techniques. They all evolve into greater complexities from the brush techniques of seal script, that is: hidden, central and returned-strokes. All other calligraphic scripts are grounded on these techniques whose simplicity in brush handling enables the writing of round and powerful strokes without exposing angles. Moreover, it is also comparatively less varied in lifting and pressing during brush manipulation, and therefore is easily grasped by a beginner.

Regular Script

Though complete in calligraphy techniques, the regular script is also complex and varied, and is therefore difficult for a beginner. Furthermore, in the olden days, the brush was used, not only in daily life but also in art creations, whereas nowadays, it is merely a tool for art. With little understanding of how to move the brush steadily, a beginner nowadays has to deal with such a variety of techniques. This leads to a confused and muddled idea about calligraphy techniques. The resulting strokes are complete in form, but dull in spirit. It is inconceivable that this calligraphy can reach the superior level.Therefore, practice seal script first, endeavoring to acquire a firm grasp of the brush manipulation, to be able to write round and powerful strokes, using the hidden, central and returned-stroke techniques. Then, there will be no problem learning any other calligraphy script. For example, with the spirit of the seal script, the running script will be sturdy and powerful; with the central-stroke of the seal script, the cursive script strokes will be graceful; and with the consolidation of the ideas in the seal and clerical scripts, the regular script can form both square and round strokes with ease.

Curvature in Seal Script

Furthermore, when lines are absolutely straight, they are dull and uninteresting. One of the main factors that dots and strokes in calligraphy are full of beauty lies in their appropriate curvature. All the five calligraphic scripts exhibit their unique curvature in different forms. Historically, famous calligraphers all possessed their distinctive styles of curvature. Thus, the implied elegance of curvature in seal script’s “straightness visible through curvature and curvature visible through straightness” is the best guideline in the practice of curvature.

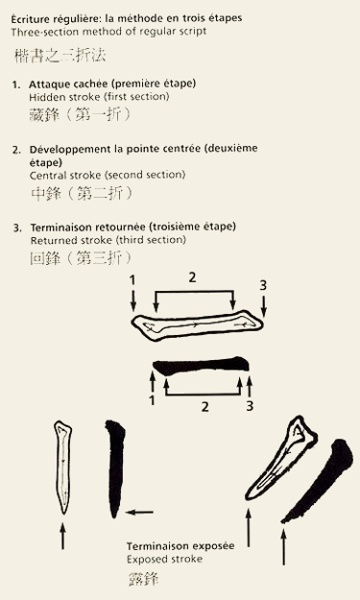

Three Sections Method and Turn

Whether or not the different shapes of dots and lines are written in round, angular or a combination of both strokes, the “three-section method” is invariably used. This means that every stroke is written in three parts. It should be noticed however that the difference between angular and round strokes involves a consequential difference in the application of the three-section method. Following is a description of the three-section method in the round strokes of seal script:

-

Hidden Stroke

For a horizontal stroke, if the intended direction is rightward, move slightly leftward first; while for a vertical stroke, if downward is intended, move slightly upward first. In either case, the tip always moves along the same straight line. Furthermore, when starting a horizontal stroke, the top of the stem should be slightly inclined to the left (toward the top of the sheet for a vertical stroke), then move slightly leftward (towards the bottom of the sheet for a vertical stroke) to the starting point of the stroke, and finally press heavily to form a round dot. At the same time, the brush stem must be slanted so that, in a horizontal stroke, the top of the brush points to the left, whereas in a vertical one, it points upward. In this way, one can easily regulate the strength applied to the tip. This is the first section. -

Central Stroke

Once a dot is formed by the hidden-stroke, lift the brush slightly, and with its hair spread out evenly, move forward to form a horizontal stroke. If moving downward, then form a vertical line. While moving, the tip should always be maintained at the same level, till it reaches the end of the strokes. This is the second section. -

Returned Stroke

At the end of a stroke, lift the tip and rapidly bring it leftward for a horizontal stroke (upward for a vertical stroke), so as to return it to the stroke to make a round ending. This is the third section. -

Making a Turn

To turn a corner in the seal script, lift the brush slightly and use central-stroke to move forward.

Chapter 7

Special Techniques for the Regular Script

Introduction

As a calligraphy teacher, I consider acquiring proficiency in the brush manipulation techniques of the seal script’s round strokes as the first step. Indeed, it paves the way for learning the clerical, regular and eventually the running and cursive scripts in sequence. On the same basis, the three-section method is also used in the regular script to describe overtly angular-round strokes with the brush techniques of hidden, central and returned- strokes. Here, I would also like to introduce regular script with which some schools of thought prefer to start. Below is the method, as applied to the regular script:

Strokes and Joints

-

Hidden Stroke

Begin a stroke by the slanting the tip, cutting in, that is: write a horizontal stroke with the tip moving vertically in, and a vertical one, horizontally in. This is called the slanting cut-in method. Here, the tip does not move forward and backward in the same straight line, as in the seal script. Therefore, start by slanting the tip till it reaches the starting point of the stroke at the upper left corner, then press to create an angular dot. At this juncture, the tip is still a little inclined, but the brush has to be raised slightly, changing the tip from the slanting position to a central one. Subsequently, incline the stem so that its top points towards the left in a horizontal stroke, but towards the upper part, in a vertical one. This will enable one’s strength to flow easily in the intended direction. This is the first section of the method. -

Central Stroke

Once the angular dot is done with the hidden-stroke, raise the tip slightly and move to the right, with the central-stroke, to complete a horizontal stroke, (downward, for a vertical one), until the end of the stroke. Depending on the style, it may sometimes be necessary to lift or press the tip while advancing. That is the second section. -

Returned Stroke

At the end of a stroke, slightly incline the tip and press it, so as to make an angular shape. Then raise it, bringing it back to the stroke. This is the third section. -

Exposed Stroke

See the explanation about the exposed-stroke in section 5 of chapter 5. If a “tick” shape is needed at the end of a stroke, then slightly lift the tip, pause momentarily, and tick to the left. -

Joints

To make an angular joint at a corner of a stroke, slightly incline the brush-tip and press. Then return to the central-stroke to continue on.

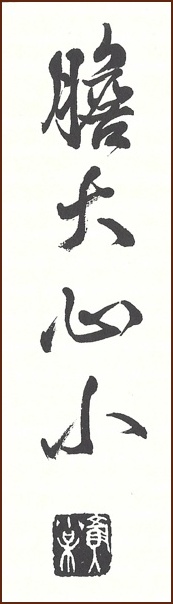

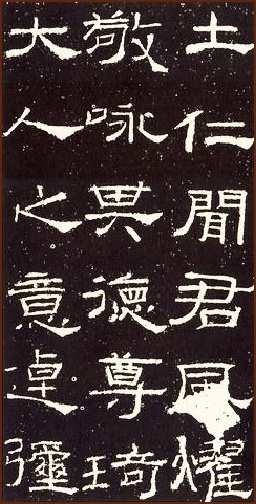

Regular Script

The Eight Elements of the Character "Eternity"

According to Wang Xi-Zhi

Regular Script

According to Wang Xi-Zhi

Regular Script

Brush Movements for the Character "Eternity"

Regular Script

Brush Movements

Regular Script

Chapter 8

The Writings of Ancient Calligraphers

Tracing, Copying and Reading

The writings by ancient calligraphers are the only ways to learn calligraphy. The history of Chinese calligraphy is so long that thousands of such writings exist which are lifetime reference to the calligrapher. A beginner must first choose one of these for practice, until all its skills are at one’s fingertips. Avoid changing from one to another at will, as this will likely slow down your progress. As the Chinese saying goes, “calligraphy cannot be learned in 100 days”. One must persevere and continue practicing in order to have achievements. On the other hand, without knowledge and training in brush manipulation techniques, even lifetime efforts in practicing calligraphy are futile. Here is a brief description of the three ways to learn from models of calligraphy.

Tracing is construed as tracing the characters on a transparent piece of paper placed over the model. It enables one to concentrate on the brush manipulation techniques, without the need to pay attention to character formation. Having undergone this process, one can easily manage to copy both the brush manipulation techniques and the character formation. Copying means to reproduce, in writing, the characters of a calligraphy model. In general, the process of tracing precedes that of copying. A beginner should choose one style of model in which every character-size approximates 5 cm2. Characters which are blurred or indistinguishable, may be skipped over. Finally, “reading” a calligraphy model means to examine all its elements, spacing, shapes and movement carefully and, from time to time, comparing your copied manuscript with it in order to deepen your understanding of calligraphy at large. Here are good models of different calligraphy scripts:

Chinese Calligraphy Masterpieces Illustrative of the Seal Script

Stone Drums of the Zhou Dynasty

Stele of Yi-Shan Mountain, Qin Dynasty

Copy by Hsü Hsüan of the Southern Tang Dynasty

Chinese Calligraphy Masterpieces Illustrative of the Clerical Script

Stele of Cao-Quan, Han Dynasty

Stele of Ritual Vessels, Han Dynasty

Chinese Calligraphy Masterpieces Illustrative of the Regular Script

Stele of Yan Qin-Li, Tang Dynasty

by Yan Zheng Xiang, Tang Dynasty

Stele of Zhang Meng-Long

Northern Wei Dynasty

Chinese Calligraphy Masterpieces Illustrative of the Running Script

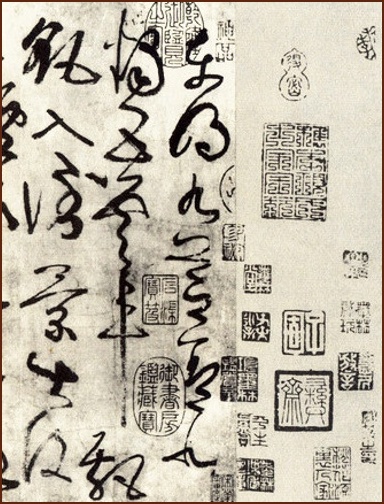

Lan-Ting Xu

by Wang Xi-Zhi, Xin Dynasty

Calligraphy on Sichuan Silk

by Mi Fei, Song Dynasty

Chinese Calligraphy Masterpieces Illustrative of the Cursive Script

Four Ancient Poems

by Zhang Xu, Tang Dynasty

Autobiography

by Monk Huai Su, Tang Dynasty

❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖

Detailed Table of Contents

- Preliminary Subjects

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 ‒ Mind Painting – Creative Energy in Calligraphy

- Legendary Origins

- Making Sense of the Legend

- Beginnings of the Chinese Brush

- Evolution of Chinese Calligraphy

- Discoveries through Observation

- Idea-Image

- Hidden Shapes of Strokes

- A Speedy Approach

- Ancient Calligraphers

- Underlying Techniques

- Ideas Precide Writing

- Chinese Calligraphies Are Not Pictures

- Mastering the Chinese Brush

- Chapter 2 ‒ Chinese Calligraphy Scripts

- Chapter 3 ‒ The Calligrapher's Tools

- Chapter 4 ‒ Watching Lady Gong-Sun's Sword Dance

- Chapter 5 ‒ Calligraphy Techniques

- Chapter 6 ‒ Approach Trough the Seal Script

- Chapter 7 ‒ Special Techniques for the Regular Script

- Chapter 8 ‒ Studying the Writings of Ancient Calligraphers

❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖ ❖

Contents: Ngan Siu-Mui

Webmaster: jy-pelletier

Tous droits réservés — All rights reserved — 版 權 所 有

顏 小 梅 (Ngan Siu-Mui) — 2004, 2022

top of the page

top of the page